Introduction

Most people have goals in their live, that if achieved, will change them in one way or the other.

However, setting ourselves goals and achieving them through chosen activities can be hard, be it by taking on too ambitious goals, live getting in the way or simply by forgetting about the new years resolution that we have written (on paper) and lost in the drawer at the start of the year.

To overcome these challenges, there are insights from science to support us in increasing the likelihood of succeeding. In my quest to set up a goal achieving support systems for myself, I have gathered tools & insights from various sources.

These include:

- A concept from the book “The 12 Week Year” by Brian Moran of setting goals for 12 weeks (instead of a year) and breaking down weekly and daily actions to achieve them.

- A subset of techniques described in the book “How to Change” by Katy Milkman.

- Insights from a Huberman Lab podcast with Dr. Emily Balcetis on how visualisations (not vision boards!) support in achieving goals.

A combination of them is formulated in the key takeaways that follow in the next paragraphs.

Structure your year into 12 week sprints

In her book “How to Change” Professor Katy Milkman talks about picking a meaningful date to start to change. Structuring your life in 12 week segments allows you to make use of this “Fresh Start Effect” at roughly four possible dates throughout the year (and saves you from training in a crammed gym on the 2nd of January).

If you have left behind your school or university years, you might notice that the existing structure of school year, vacation and semesters has dissolved into less clear endings and beginnings. With 4 cycles of 12 weeks, you impose on yourself a structure to work on your goals and commitments.

Lastly, sticking for 12 weeks with an activity allows you to have more frequent variety in the things you do. For instance, you might enjoy to change your sport goal from weight-training to running from one cycle to the other. Starting new things or coming back to them after a while allows you to have the repeated steep learning curve of beginnings and the satisfaction that comes with it. After all, the goals we set for ourselves are oftentimes only relevant to us, so why not make them as fun as possible.

To broadcast or not your goals to the public

Sharing your goals with a friends or relatives might not actually be beneficial for achieving them. By the reactions and approvals you get by merely telling others, you might be already satisfied and therefore less driven to get into the action it takes to change in the pursuit of the goal.

Thus, when broadcasting your goals, beware to choose wisely how to share them. A good solution to alleviate this effect is to combine the sharing with methods which parallely impose accountability.

For instance, the “Cash Commitment Devices” from “How to Change” can be used, where the stakes are increased by giving away money if a goal is not achieved or you don’t perform a promised activity. There are well known tools for this (such as stickK) where users can choose to give money to charity (or an anti-charity).

Other soft commitments such as pledges can also be beneficial, with the remaining importance of attaching accountability, e.g. by public display of the pledge on social media.

How to effectively use visualisation

Interestingly, the use of vision boards seem to have similar effects than previously described process of telling people. Physiologically, they give you the (wrong) satisfaction of having achieved your goal, which in turn leaves you without the resources to get into action.

As described by Emily Balcetis, there is no fault in using them, however the follow up steps to the vision board should be to:

- break them down into manageable goals

- and identify the obstacles that might arise during executing the actions to achieve the goal.

Which nicely aligns with the methods given in both “The 12 Week Year” and “How to Change”.

Another interesting insight from this podcast episode is that for physical activity, narrowing your field of vision on an intermediate target (in the distance) can actually help you to push harder, reduce the perception of pain and help you get into a flow state.

For non-physical goals, this somewhat translates into having a clear vision on how you are performing and “keeping the goal”. Tracking progress can help to give you a more objective view, since your memory might be skewed to over- or underestimate your performance.

Practical tips

- I use Obsidian for tracking my goals. In there, I have:

- A habit tracker for a visual representation of daily habits, of which a detailed guide can be found here: Obsidian Habit & Mood Tracker - CssRepo

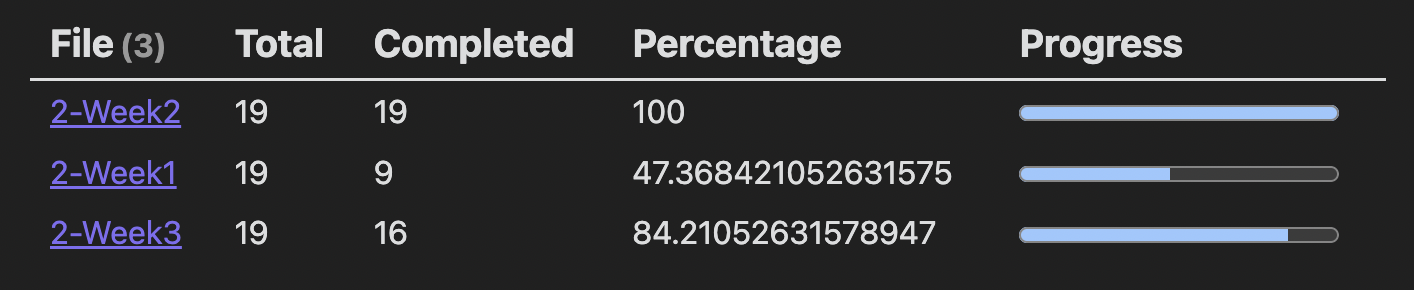

- And I include progress bars into my daily notes, using dataview.js, to get a sense of how I am doing in the grand scheme of things in completing the actions to complete my 12 week goals. I might go into details on how to build it in a future post.

- Another nice and simple tracking (iPhone) app is Momentum

Links

- Huberman Lab - Dr. Emily Balcetis: Tools for Setting & Achieving Goals

- Podcast notes to the episode

- The 12 Week Year of which I would recommend to only read a summary.

- How to Change: The Science of Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be

- Goal Setting: A Scientific Guide to Setting and Achieving Goals for further reading.